Red Planet, by Robert A. Heinlein

2026-02-20 17:04Second paragraph of third chapter:

The temperature was rising and the dawn wind was blowing firmly, but it was still at least thirty below. Strymon canal was a steel-blue, hard sheet of ice and would not melt today in this latitude. Resting on it beside the dock was the mail scooter from Syrtis Minor, its boat body supported by razor-edged runners. The driver was still loading it with cargo dragged from the warehouse on the dock.

Published in 1949, this was a book that I greatly enjoyed as a young reader, one of Heinlein’s successful juvenile series. The protagonist is a lad in the human colony on Mars, attending a military boarding school where he discovers a fiendish plot by the Earth-based rulers to destroy the colonists. Aided by his Martian pet, and by the mysterious giant Martians themselves, he gets home via the canals and other Martian tech, raises the alarm and helps his family and the rest of the colony defeat the evil administrators, who are apparently eaten by the Martians.

It’s a very male book; the protagonist and his buddy, and their fathers and a wise old doctor, carry most of the narrative, with some dialogue from mothers and a bratty sister. It’s a very pro-gun book; the colonists’ equivalent of Second Amendment rights are taken as obvious common sense (and of course crucial in the uprising). The colonists’ mission is explicitly colonial; no questions are asked about the fate of the Martians once humans spread out over the planet.

And yet there’s still a very attractive sensawunda about it, a feeling of estrangement from Earth and awe at the ancient mysteries and dangers of a new world, and arid landscapes not quite like the American West. Some of the magic remains for me, though perhaps not quite enough for me to recommend it to readers of the same age as I was when I first read it. You can get Red Planet here.

This was my top unread sf book (though of course I had read it long ago). Next on that pile is Trouble with Lichen, by John Wyndham.

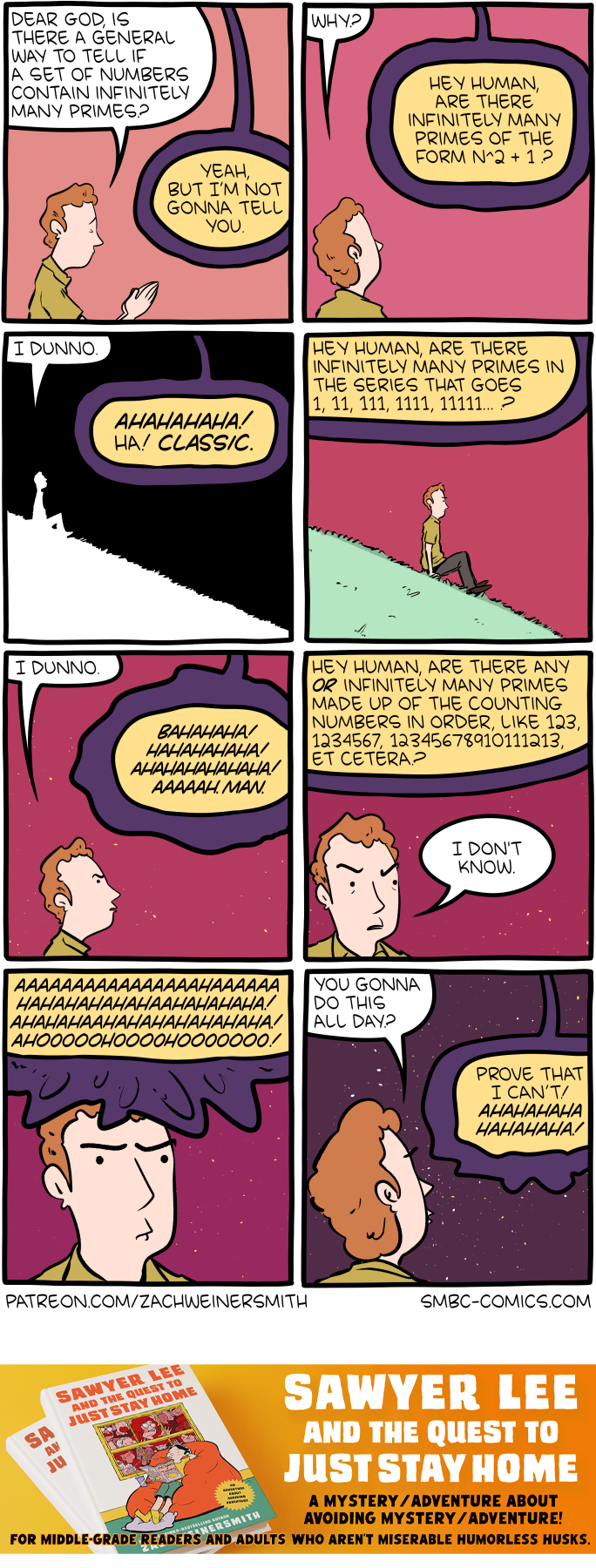

Saturday Morning Breakfast Cereal - Prime

2026-02-20 11:20

Click here to go see the bonus panel!

Hovertext:

Unrelated, but according to Maynard 2019 there's an infinite number of primes that don't require the letter W.

Today's News:

Namecheap abandons fight for .org price caps

2026-02-20 15:12Namecheap seems to have thrown in the towel in its long-running fight to get ICANN to cap the prices of .org and .info domain names. The registrar terminated its Independent Review Process complaint against ICANN back in November, with the IRP panel formally closing the case December 16, according to documents ICANN published last week. […]

The post Namecheap abandons fight for .org price caps first appeared on Domain Incite.

- 2026‑02‑20 - Banish: a declarative DSL embedded in Rust, for defining rule-based state machines.

- https://github.com/LoganFlaherty/banish

- redirect https://dotat.at/:/Q56VS

- blurb https://dotat.at/:/Q56VS.html

- atom entry https://dotat.at/:/Q56VS.atom

- web.archive.org archive.today

25 Years in Ohio

2026-02-20 14:11

February marks an anniversary for us: in this month in 2001, Krissy and Athena and I moved to this house in Bradford, Ohio, so now we have been citizens of this village and state for 25 years. On the 20th anniversary, I wrote a long piece about moving here and what that meant to us, and that’s still largely accurate, so I’m not going to replicate here. I will note that in the last five years, we’ve become even more entrenched here in Bradford, as we went on a bit of a real estate spree, purchasing a church, a campground, and a few other properties, and started a business and foundation here in town as well. We’ve become basically (if not technically precisely) the 21st century equivalent of landed gentry.

It’s possibly fitting that after a quarter century here in rural Ohio, I finally wrote a novel that takes place in it, which will be out, as timing would have it, on election day this year. The town in the novel is fictional but the county is real, as it my own, and it’s been interesting writing something about this place, now — that also, you know, has monsters in it. I certainly hope people around here are going to be okay with that, rather than, say, “you wrote what now about us?” There is a reason I made a fictional town, mind you.

I continue to be a bit of an odd duck for the area, which I don’t see changing, and despite the fact the number of full-time writers in Bradford has doubled thanks to Athena. On the other hand, as I’ve noted before, my output is such that Bradford is the undisputed literary capital of Darke County, and I think that’s something both Bradford and Darke County can be proud of.

Anyway, Ohio, and Darke County, and Bradford, have been good to me in the last quarter century. I hope I have been likewise to them. We’re likely to stay.

— JS

The Doctor does Oscar Wilde

2026-02-20 14:23The Friend Zone Experiment by Zen Cho

2026-02-20 09:10

A successful businesswoman has the opportunity of a lifetime offered to her, only to have an old friend greatly complicate matters.

The Friend Zone Experiment by Zen Cho

The perils of ISBN.

2026-02-19 17:25- 2026‑02‑19 - The perils of ISBN.

- https://rygoldstein.com/posts/perils-of-isbn

- redirect https://dotat.at/:/U7VPF

- blurb https://dotat.at/:/U7VPF.html

- atom entry https://dotat.at/:/U7VPF.atom

- web.archive.org archive.today

Tue 24 Feb 14:00: Digital platforms and health disinformation

2026-02-20 11:42

Digital platforms and health disinformation

This talk will discuss the role of digital platforms in providing the infrastructure through which health disinformation is advertised and circulated. The presentation will examine several case studies exploring how platforms are leveraged to promote and spread disinformation surrounding scientifically unsupported cancer treatments. Platforms examined will include Google keyword advertising, Meta (Facebook and Instagram) ads, Google Reviews, Amazon marketplaces, and crowdfunding platforms such as GoFundMe. The talk will emphasize moving away from blaming individuals and toward building accountable systems that prevent, mitigate, and respond to disinformation, while strengthening platform accountability.

Bio: Marco Zenone (he/him) is an Assistant Professor of Health Science Communication at the Faculty of Health Sciences, University of Ottawa. His research examines the spread, impact, and political economy of health misinformation and disinformation, as well as how health topics are portrayed across digital platforms and public spaces. A major focus is examining digital platforms as commercial determinants of health and how their infrastructures shape the production, circulation, and visibility of health disinformation. His research emphasizes moving beyond individual blame toward building accountable systems that prevent, mitigate, and respond to health disinformation.

- Speaker: Marco Zenone, University of Ottawa

- Tuesday 24 February 2026, 14:00-15:00

- Venue: Webinar & FW11, Computer Laboratory, William Gates Building..

- Series: Computer Laboratory Security Seminar; organiser: Alexandre Pauwels.

Interesting Links for 20-02-2026

2026-02-20 12:00- 1. Looksmaxxing: Myth Vs. Fact

- (tags:funny trends beauty society bodyimage )

- 2. An excellent break down of the EHRC trangender toilet case, and the High Court findings. It is, as you might expect, a mess.

- (tags:law transgender uk lgbt )

- 3. Sizing chaos - an incredibly visualised look at how and why women's clothes sizing is a mess that lets down half of all women

- (tags:women clothing visualisation OhForFucksSake history society )

- 4. Psychology of Gen X Parents (I feel called out. Or described. Or something)

- (tags:psychology demographics history video )

- 5. What is Going on with Colorectal Cancer in young people?

- (tags:cancer age statistics )

Fri 06 Mar 12:00: Title to be confirmed

2026-02-20 10:44Title to be confirmed

Abstract not available

- Speaker: Mario Giulianelli (UCL)

- Friday 06 March 2026, 12:00-13:00

- Venue: SS02 Hybrid (In-Person + Online). Here is the Google Meet Link: https://meet.google.com/cru-hcuo-rhu.

- Series: NLIP Seminar Series; organiser: Suchir Salhan.

Fri 27 Feb 12:00: What Happens When They're Smarter Than Us?

2026-02-20 10:42What Happens When They're Smarter Than Us?

Abstract: We are building machine learning models that outperform humans on particular tasks, from coding to mathematics. But what do we mean when we talk about AI capabilities, and how can we ensure AI systems remain aligned with human interests as they become more capable than us? I develop an account of capabilities as dispositional properties, analogous to fragility or solubility, where a capability is characterised by a mapping from task demands to behavioural probabilities. This framing clarifies why we should expect some capabilities to scale beyond human levels, which creates attendant risks. Systems more capable than their overseers might learn to exploit this capability gap – a form of principal-agent problem. I show that a promising protocol, debate, is vulnerable to this problem. I then present a potential solution: replacing single judges with juries. I outline the cases under which this extension works and the ways in which it can break down.

Speaker Bio: Dr Konstantinos Voudouris is the cognitive scientist on the Alignment Team at the UK AI Security Institute. He holds a PhD in psychology (2024) from the University of Cambridge. His research focuses on advancing the sciences of AI alignment, scalable oversight, and AI evaluation, using tools from the cognitive sciences. Combining these diverse fields allows us to build better, safer, and more human-like AI systems, as well as informed and sensible AI policy.

- Speaker: Dr Konstantinos Voudouris (UK AI Security Institute)

- Friday 27 February 2026, 12:00-13:00

- Venue: SS02 Hybrid (In-Person + Online). Here is the Google Meet Link: https://meet.google.com/cru-hcuo-rhu.

- Series: NLIP Seminar Series; organiser: Suchir Salhan.

CHERIoT Rust status update #0.

2026-02-19 02:21- 2026‑02‑19 - CHERIoT Rust status update #0.

- https://rust.cheriot.org/2026/02/15/status-update.html

- redirect https://dotat.at/:/7IRP2

- blurb https://dotat.at/:/7IRP2.html

- atom entry https://dotat.at/:/7IRP2.atom

- web.archive.org archive.today

Parsing hours and minutes into a useful time in basic Python

2026-02-20 03:48Suppose, not hypothetically, that you have a program that optionally takes a time in the past to, for example, report on things as of that time instead of as of right now. You would like to allow people to specify this time as just 'HH:MM', with the meaning being that time today (letting people do 'program --at 08:30'). This is convenient for people using your program but irritatingly hard today with the Python standard library.

(In the following code examples, I need a Unix timestamp and we're working in local time, so I wind up calling time.mktime(). We're working in local time because that's what is useful for us.)

As I discovered or noticed a long time ago, the time module is a thin shim over

the C library time functions and inherits

their behavior. One of these behaviors is that if you ask

time.strptime() to parse

a time format of '%H:%M', you get back a struct_time

object that is in 1900:

>>> import time

>>> time.strptime("08:10", "%H:%M")

time.struct_time(tm_year=1900, tm_mon=1, tm_mday=1, tm_hour=8, tm_min=10, tm_sec=0, tm_wday=0, tm_yday=1, tm_isdst=-1)

There are two solutions I can think of, the straightforward brute force approach that uses only the time module and a more theoretically correct version using datetime, which comes in two variations depending on whether you have Python 3.14 or not.

The brute force solution is to re-parse a version of the time string with the date added. Suppose that you have a series of time formats that people can give you, including '%H:%M', and you try them all until one works, with code like this:

for fmt in tfmts:

try:

r = time.strptime(tstr, fmt)

# Fix up %H:%M and %H%M

if r.tm_year == 1900:

dt = time.strftime("%Y-%m-%d ", time.localtime(time.time()))

# replace original r with the revised one.

r = time.strptime(dt + tstr, "%Y-%m-%d "+fmt)

return time.mktime(r)

except ValueError:

continue

I think the correct, elegant way using only the standard library is to use datetime to combine today's date and the parsed time into a correct datetime object, which can then be turned into a struct_time and passed to time.mktime. Before Python 3.14, I believe this is:

r = time.strptime(tstr, fmt)

if r.tm_year == 1900:

tm = datetime.time(hour=r.tm_hour, minute=r.tm_min)

today = datetime.date.today()

dt = datetime.datetime.combine(today, tm)

r = dt.timetuple()

return time.mktime(r)

There are variant approaches to the basic transformation I'm doing here but I think this is the most correct one.

If you have Python 3.14 or later, you have datetime.time.strptime() and I think you can do the slightly clearer:

[...]

tm = datetime.time.strptime(tstr, fmt)

today = datetime.date.today()

dt = datetime.datetime.combine(today, tm)

r = dt.timetuple()

[...]

If you can work with datetime.datetime objects, you can skip converting back to a time.struct_time object. In my case, the eventual result I need is a Unix timestamp so I have no choice.

You can wrap this up into a general function:

def strptime_today(tstr, fmt):

r = time.strptime(tstr, fmt)

if r.tm_year != 1900:

return r

tm = datetime.time(hour=r.tm_hour, minute=r.tm_min, second=r.tm_sec)

today = datetime.date.today()

dt = datetime.datetime.combine(today, tm)

return dt.timetuple()

This version of time.strptime() will return the time today if given a time format with only hours, minutes, and possibly seconds. Well, technically it will do this if given any format without the year, but dealing with all of the possible missing fields is left as an exercise for the energetic, partly because there's no (relatively) reliable signal for missing months and days the way there is for years. For many programs, a year of 1900 is not even close to being valid and is some sort of mistake at best, but January 1st is a perfectly ordinary day of the year to care about.

(Now that I've written this function I may update my code to use it, instead of the brute force time package only version.)

Panic in Year Zero

2026-02-20 09:041962 science fiction, dir. and starring Ray Milland, Jean Hagen, Frankie Avalon: IMDb. The family is heading out for a camping trip, when the sky behind them starts to look very strange…

Start Up No.2614: sorry, not possible today.

2026-02-20 07:00For unknown reasons, WordPress has changed the way it responds to curl queries in an unexpected and unannounced way which breaks the script I use to compose The Overspill.

This is yet another obstacle WordPress has put in my way over the past decade. Pages are changed, responses altered (or not given) in ways which break scripts that are usually quite robust. It’s a constant, low-level annoyance.

I’ve been unable to figure out how WordPress has broken my script despite an hour or so of efforts. A script that has run perfectly for a number of years doesn’t now work, and it’s too late at night to spend any more time on it.

I will try to fix this. But I don’t know what I’ll do if I can’t. (Just for added fun, WordPress refused to accept this from my normal blogpost editor.)

At least there’s an answer to one question: what was the blogpost I was looking for about sizing women’s clothes, posted after 2010, by a woman, with “green” somewhere in the name? Thanks Struan D for the answer:

https://sizes.darkgreener.com/ is the one. THIS is the project I was thinking of: Anna Powell-Smith’s 2012 (after 2010 as I said!) project at darkgreener (contains green in the name!) about dress sizes. As she notes at her site, it’s her only work that’s been featured in both the Wall Street Journal and the Daily Mail. She’s now the director of the Centre for Public Data, an advocacy organisation. Thanks Struan D for the link; no thanks to search engines or chatbots. Humans win again!

The Internet Isn’t Facebook: How Openness Changes Everything

2026-02-20 00:00“Open” tends to get thrown around a lot when talking about the Internet: Open Source, Open Standards, Open APIs. However, one of the most important senses of the Internet’s openness doesn’t get discussed as much: its openness as a system. It turns out this has profound effects on both the Internet’s design and how it might be regulated.

This critical aspect of the Internet’s architecture needs to be understood more now than ever. For many, digital sovereignty is top-of-mind in the geopolitics of 2026, but some conceptions of it treat openness as a bug, not a feature. The other hot topic – regulation to address legitimately-perceived harms on the Internet – can put both policy goals and the value we get from the Internet at risk if it’s undertaken in a way that doesn’t account for the openness of the Internet. Properly utilised, though, the power of openness can actually help democracies contribute to the Internet (and other technologies like AI) in a constructive way that reinforces their shared values.

Open and Shut

Most often, people think and work within closed systems – those whose boundaries are fixed, where internal processes can be isolated from external forces, and where power is concentrated hierarchically. That single scope can still embed considerable complexity, but the assumptions that its closed nature allows make certain skills, tools, and mindsets advantageous. This simplification helps compartmentalise effects and reduces interactions; it’s easier when you don’t have to deal with things you don’t (and can’t) know, much less control.

Many things we interact with daily are closed – for example, a single company, a project group, or even a legal jurisdiction. The Apple App Store, air traffic control, bank clearing systems, and cable television networks are closed; so are many of the emerging AI ecosystems.

The Internet is not like that.

That’s because it’s not possible to know or control all of the actors and forces that influence and interact with the Internet. New applications and networks appear daily, without administrative hoops; often, this is referred to as “permissionless innovation,” which allowed things the Web and real-time video to be built on top of the network without asking telecom operators for approval. New protocols and services are constantly proposed, implemented and deployed – sometimes through an SDO like the IETF, but often without any formal coordination.

This is an open system, and it’s important to understand how that openness constrains the nature of what’s possible on the Internet. What works in a closed system falls apart when you try to apply it to the Internet. Openness as a system makes introducing new participants and services very easy – and that’s a huge benefit – but that open nature makes other aspects of managing the ecosystem very different (and sometimes difficult). Let’s look at a few.

Designing for Openness

Designing an Internet service like an online shop is easy if you assume it’s a closed ecosystem with an authority that ‘runs’ the shop. Yes, you have to deal with accounts, and payments, and abuse, and all of the other aspects, but the issues are known and can be addressed with the right amount of capital and a set of appropriate professionals.

For example, designing an open trading ecosystem where there is no single authority lurking in the background and making sure everything runs well is an entirely different proposition. You need to consider how all of the components will interact and at the same time assure that none is inappropriately dominated by a single actor or even a small set, unless there are appropriate constraints on their power. You need to make sure that the amount of effort needed to join the system is low, while at the same time fighting the abusive behaviours that leverage that low barrier, such as spam.

This is why regulatory efforts that are focused on reforming currently closed systems – “opening them up” by compelling them to expose APIs and allow competitors access to their systems – are unlikely to be successful, because those platforms are designed with assumptions that you can’t take for granted when building an open system. I’ve written previously about Carliss Baldwin’s excellent work in this area, primarily from an economic standpoint. An open system is not just a closed one with a few APIs grafted onto it.

For example, you’re likely to need a reputation system for vendors and users, but it can’t rely on a single authority making judgment calls about how to assign reputation, handle disputes, and so forth. Instead, you’ll want to make it more modular, where different reputation systems can compete. That’s a very different design task, and it is undoubtedly harder to achieve a good outcome.

At the same time, an open system like the Internet needs to be more pessimistic in its assumptions about who is using it. While closed systems can take drastic steps like excluding bad actors from them, this is much more difficult (and problematic) in an open system. For example, a closed shopping site will have a definitive list of all of its users (both buyer and seller) and what they have done, so it can ascertain how trustworthy they are based upon that complete view. In an open system, there is no such luxury – each actor only has a partial view of the system.

Introducing Change in Open Systems

An operator of a proprietary, closed service like Amazon, Google, or Facebook has a view of its entire state and is able to deploy changes across it, even if they break assumptions its users have previously relied upon. Their privileged position gives them this ability, and even though these services run on top of the Internet, they don’t inherit its openness.

In contrast, an open system like e-mail, federated messaging, or Internet routing is much harder to evolve, because you can’t create a list of who’s implementing or using a protocol with any certainty; you can’t even know all of the ways it’s being used. This makes introducing changes tricky; as is often said in the IETF, you can’t have a protocol ‘flag day’ where everyone changes how they behave at the same time. Instead, mechanisms for gradual evolution (extensibility and versioning) need to be carefully built into the protocols themselves.

The Web is another example of an open system.1 No one can enumerate all of the Web servers in the world – there are just too many, some hidden behind firewalls and logins. There are whole social networks and commerce sites that you’ve never heard of in other parts of the world. While search engines make us feel like we see the whole Web (and have every incentive to make us believe that), it’s a small fraction of the real thing that misses the so-called ‘deep’ Web. This vastness is why browsers have to be so conservative in introducing changes, and why we have to be so careful when we update the HTTP protocol.

Governing Open Systems

Openness also has significant implications for governance. Command-and-control techniques that work well when governing closed systems are ineffective on an open one, and can often be counterproductive.

At the most basic level, this is because there is no single party to assign responsibility to in an open system – its governance structure is polycentric (i.e., has multiple and often diffuse centres of power). Compounding that effect is the fact that large open systems like the Internet span multiple jurisdictions, so a single jurisdiction is always going to be playing “whack-a-mole” if it tries to enforce compliance on one party. As a result, decisions in open systems tend to take much more time and effort than anticipated if you’re used to dealing with closed, hierarchical systems.

On the Internet, another impact of openness is seen in the tendency to create “building block” technology components that focus on enabling communication, not limiting it. That means that they are designed to support broad requirements from many kinds of users, not constrain them, and that they’re composed into layers which are distinct and separate. So trying to use open protocols to regulate behaviour of Internet users is often like trying to pin spaghetti to the wall.

Consider, for example, the UK’s attempts to regulate user behaviour by regulating lower-layer general-purpose technologies like DNS resolvers. Yes, they can make it more difficult for those using common technology to do certain things, but actually stopping such behaviour is very hard, due to the flexible, layered nature of the Internet; determined people can do the work and use alternative DNS servers, encrypted DNS, VPNs, and other technologies to work around filters. This is considered a feature of a global communications architecture, not a bug.

That’s not to say that all Internet regulation is a fools’ errand. The EU’s Digital Markets Act is targeting a few well-identified entities who have (very successfully) built closed ecosystems on top of the open Internet. At least from the perspective of Internet openness, that isn’t problematic (and indeed might result in more openness).

On the other hand, the Australian eSafety Regulator’s effort to improve online safety – itself a goal not at odds with Internet openness – falls on its face by applying its regulatory mechanisms to all actors on the Internet, not just a targeted few. This is an extension of the “Facebook is the Internet” mindset – acting as if the entire Internet is defined by a handful of big tech companies. Not only does that create significant injustice and extensive collateral damage, it also creates the conditions for making that outcome more likely (surely a competition concern). While these closed systems might be the most legible part of the Internet to regulators, they shouldn’t be mistaken for the Internet itself.

Similarly, blanket requirements to expose encrypted messages have the effect of ‘chasing’ criminals to alternative services, making their activity even less legible to authorities and severely impacting the security and rights of law-abiding citizens in the process. That’s because there is no magical list of all of the applications that use encryption on the Internet: instead, regulators end up playing whack-a-mole. Cryptography relies on mathematical concepts realised in open protocols; treating encryption as a switch that companies can simply turn off misses the point.

None of this is new or unique to the Internet; cross-border institutions are by nature open systems, and these issues come up often in discussions of global public goods (whether it is oceans, the climate, or the Internet). They thrive under governance that focuses on collaboration, diversity, and collective decision-making. For those that are used to top-down, hierarchical styles of governance, this can be jarring, but it produces systems that are far more resilient and less vulnerable to capture.

Why the Internet Must Stay Open

If you’ve read this far, you might wonder why we bother: if openness brings so many complications, why not just change the Internet so that it’s a simpler, closed system that is easier to design and manage? Certainly, it’s possible for large, world-spanning systems to be closed. For example, both the international postal and telephony systems are effectively closed (although the latter has opened up a bit). They are reliable and successful (for some definition of success).

I’d argue that those examples are both highly constrained and well-defined; the services they provide don’t change much, and for the most part new participants are introduced only on one ‘side’ – new end users. Keeping these networks going requires considerable overhead and resources from governments around the world, both internally and at the international coordination layer.

The Internet (in a broader definition) is not nearly so constrained, and the bulk of its value is defined by the ability to introduce new participants of all kinds (not just users) without permission or overhead. This isn’t just a philosophical preference; it’s embedded in the architecture itself via the end-to-end principle. Governing major aspects of the Internet by international treaty is simply unworkable, and if the outcome of that agreement is to limit the ability of new services or participants to be introduced (e.g., “no new search engines without permission”), it’s going to have a material effect on the benefits that humanity has come to expect from the Internet. In many ways, it’s just another pathway to centralization.

Again, all of this is not to say that closed systems on top of the Internet shouldn’t be regulated – just that it needs to be done in a way that’s mindful of the open nature of the Internet itself. The guiding principle is clear: regulate the endpoints (applications, hosts, and specific commercial entities), not the transit mechanisms (the protocols and infrastructure). From what’s happened so far, it looks like many governments understand that, but some are still learning.

Likewise, the many harms associated with the Internet need both technical and regulatory solutions; botnets, DDoS, online abuse, “cybercrime” and much more can’t be ignored. However, solutions to these issues must respect the open nature of the Internet; even though their impact on society is heavy, the collective benefits of openness – both social and economic – still outweigh them; low barriers to entry ensure global market access, drive innovation, and prevent infrastructure monopolies from stifling competition.

Those points acknowledged, I and many others are concerned that regulating ‘big tech’ companies may have the unintended side effect of ossifying their power – that is, blessing their place in the ecosystem and making it harder for more open systems to displace them. This concentration of power isn’t an accident; commercial entities have a strong economic incentive to build proprietary walled gardens on top of open protocols to extract rent. For example, we’d much rather see global commerce based upon open protocols, well-thought-out legal protections, and cooperation, rather than overseen (and exploited) by the Amazon/eBay/Temu/etc. gang.

Of course, some jurisdictions can and will try to force certain aspects of the Internet to be closed, from their perspective. They may succeed in achieving their local goals, but such systems won’t offer the same properties as the Internet. Closed systems can be bought, coerced, lobbied into compliance, or simply fail: their hierarchical nature makes them vulnerable to failures of leadership. The Internet’s openness makes it harder to maintain and govern, but also makes it far more resilient and resistant to capture.

Openness is what makes the Internet the Internet. It needs to be actively pursued if we want the Internet to continue providing the value that society has come to depend upon from it.

Thanks to Konstantinos Komaitis for his suggestions.

-

Albeit one that is the foundation for a number of very large closed systems. ↩

Daily Hacker News for 2026-02-19

2026-02-20 00:00The 10 highest-rated articles on Hacker News on February 19, 2026 which have not appeared on any previous Hacker News Daily are:

-

Zero-day CSS: CVE-2026-2441 exists in the wild

(comments) -

Tailscale Peer Relays is now generally available

(comments) -

Cosmologically Unique IDs

(comments) -

27-year-old Apple iBooks can connect to Wi-Fi and download official updates

(comments) -

Sizing chaos

(comments) -

Anthropic officially bans using subscription auth for third party use

(comments) -

Gemini 3.1 Pro

(comments) -

Show HN: Micasa – track your house from the terminal

(comments) -

Gemini 3.1 Pro

(comments) -

AI makes you boring

(comments)

Friday 20 February, 2026

2026-02-20 00:41Potter mania

Every time I come through King’s Cross, it’s like this. Has there ever been anything as enduring as Harry Potter’s fandom?

Quote of the Day

”When somebody says it’s not about the money, it’s about the money.”

- H.L. Mencken

Musical alternative to the morning’s radio news

A. Vivaldi / N. Chédeville | Op. 13 n. 4 – Sonata for oboe & b.c. in A major (RV 59) | P. Goodwin

New to me, but gorgeous.

Long Read of the Day

The left is missing out on AI

Really perceptive essay by Dan Kagan-Kans on how the Left — and academia — are making big mistakes in underestimating AI technology. I was particularly struck by this passage:

Publishing in journals requires peer review, and peer review is slow. As Zvi Mowshowitz, who writes perhaps the world’s most exhaustive newsletter on AI, said, “Nobody in real academia can adhere to their norms and actually be in the conversation, because by the time you’re publishing, everything you were trying to say is irrelevant,” a generation or two behind the cutting edge. Another incentive for researchers to leave for industry, then.

This splitting of a field that once would have been forced to coexist has probably made industry too optimistic about the pace of progress and made academia too skeptical. That then skews what’s heard by people who listen to academia but not industry — and nearly everyone with that tendency, today, is on the left. They hear only the skeptics, unaware that real science is taking place in the AI labs too (or especially), done by PhD’d researchers they might trust if only they sat in a faculty office.

Books, etc.

Robert Louis Stevenson’s 1879 book, Travels with a Donkey in the Cévennes, is an utter delight. I was first alerted to it by his biographer, Richard Holmes in his book, Footsteps: Adventures of a romantic biographer, the first chapter of which recounts how he set out in 1964 to walk 220km through the Cévennes in Stevenson’s footsteps.

It’s an irresistible read, so I started on it again, and laughed out loud when reading his account of his first day on the journey. So here it is:

In an odd way, the star of Stevenson’s account of his journey is not him but the little donkey he purchased to accompany him and carry his baggage. She was, he wrote, the size of “a large Newfoundland dog” and the colour of “an ideal mouse”. He christened her Modestine and then discovered that she was an awkward character who “refused to climb hills,… shed her saddle-bag at the least provocation,… and in villages swerved into the cool of the beaded shop-doors”. He wrote that he often had to beat her with a stick (about which he felt increasingly guilty) and wept when he sold her at the end of his journey.

So when I think of RLS it’s Modestine who always comes to my mind. Accordingly, when we bought a Tesla in 2020 and discovered that we could give it a name, I of course chose Modestine, because the vehicle can, at times, appear to have a mind of its own.

Screenshot

This puzzled our friends, but I felt it was vindicated when one day I saw my wife — normally the politest person in any room — impatiently thumping the steering wheel and shouting “Come on, you stupid donkey”.

You may wonder what propelled me down this particular rabbit hole. It was just a travel piece in the weekend edition of the Financial Times about a couple who had just walked the trail courtesy of a company called Macs Adventure (two-week trip on the full trail from £1,795).

As Miss Jean Brodie famously observed about chemistry, “For those that like that kind of thing, that is the thing they like.”

Linkblog

Something I noticed, while drinking from the Internet firehose.

- Mark Zuckerberg overruled 18 wellbeing experts to keep beauty filters on Instagram

Hannah Murphy, writing in yesterday’s Financial Times:

Mark Zuckerberg told a jury on Wednesday that he overruled concerns about teen wellbeing from staff and 18 experts to lift a ban on Instagram beauty filters because he was concerned about “free expression”.

The billionaire social media boss faced a grilling in a Los Angeles court on Wednesday as he battles a landmark legal claim that social media is addictive to children.

Instagram temporarily suspended beauty filters — which digitally alter people’s appearance — to conduct a review of the features in 2019. All of the 18 experts Meta hired concluded they presented a wellbeing issue.

Zuckerberg told the court there was a “high bar” for demonstrating harm, calling the restrictions “paternalistic” and “overbearing”, adding he “wanted to err on the side of people being able to express themselves” in making the decision.

As usual, he ‘erred’ on the side of profitability and growth.

Feedback

David Ballard was struck by Monday’s Quote of the Day in which OpenAI’s Sam Altman said:

”I think that AI will probably, most likely, sort of lead to the end of the world. But in the meantime, there will be great companies created with serious machine learning.”

It reminded him of a lovely New Yorker cartoon which (I think) came out sometime during the pandemic lockdown.

Screenshot

This Blog is also available as an email three days a week. If you think that might suit you better, why not subscribe? One email on Mondays, Wednesdays and Fridays delivered to your inbox at 5am UK time. It’s free, and you can always unsubscribe if you conclude your inbox is full enough already!

RPKI’s 2025 year in review

2026-02-19 22:50IPv6 Adoption in 2026

2026-02-19 17:54[food] the kale thing

2026-02-19 22:35I have introduced my mother to this, I have introduced the Child's household to this, I am writing it down because clearly It Is Time for me to do so.

( Read more... )

Linux CVE assignment process.

2026-02-19 16:52- 2026‑02‑19 - Linux CVE assignment process.

- http://www.kroah.com/log/blog/2026/02/16/linux-cve-assignment-process/

- redirect https://dotat.at/:/IP976

- blurb https://dotat.at/:/IP976.html

- atom entry https://dotat.at/:/IP976.atom

- web.archive.org archive.today

Tall brick buildings

2026-02-19 21:10Jenners Depository. This reminds me of a different tall red-brick warehouse building that my memory places on the way east into Truro along the A39. However, some looking online fails so badly to find anything of the kind that I have probably somewhat misplaced it. It's some consolation that some further poking around online reveals that what I saw on the train into work recently was Niddry Castle.

Rust participates in Google Summer of Code 2026

2026-02-19 00:00We are happy to announce that the Rust Project will again be participating in Google Summer of Code (GSoC) 2026, same as in the previous two years. If you're not eligible or interested in participating in GSoC, then most of this post likely isn't relevant to you; if you are, this should contain some useful information and links.

Google Summer of Code (GSoC) is an annual global program organized by Google that aims to bring new contributors to the world of open-source. The program pairs organizations (such as the Rust Project) with contributors (usually students), with the goal of helping the participants make meaningful open-source contributions under the guidance of experienced mentors.

The organizations that have been accepted into the program have been announced by Google. The GSoC applicants now have several weeks to discuss project ideas with mentors. Later, they will send project proposals for the projects that they found the most interesting. If their project proposal is accepted, they will embark on a several months long journey during which they will try to complete their proposed project under the guidance of an assigned mentor.

We have prepared a list of project ideas that can serve as inspiration for potential GSoC contributors that would like to send a project proposal to the Rust organization. However, applicants can also come up with their own project ideas. You can discuss project ideas or try to find mentors in the #gsoc Zulip stream. We have also prepared a proposal guide that should help you with preparing your project proposals. We would also like to bring your attention to our GSoC AI policy.

You can start discussing the project ideas with Rust Project mentors and maintainers immediately, but you might want to keep the following important dates in mind:

- The project proposal application period starts on March 16, 2026. From that date you can submit project proposals into the GSoC dashboard.

- The project proposal application period ends on March 31, 2026 at 18:00 UTC. Take note of that deadline, as there will be no extensions!

If you are interested in contributing to the Rust Project, we encourage you to check out our project idea list and send us a GSoC project proposal! Of course, you are also free to discuss these projects and/or try to move them forward even if you do not intend to (or cannot) participate in GSoC. We welcome all contributors to Rust, as there is always enough work to do.

Our GSoC contributors were quite successful in the past two years (2024, 2025), so we are excited what this year's GSoC will bring! We hope that participants in the program can improve their skills, but also would love for this to bring new contributors to the Project and increase the awareness of Rust in general. Like last year, we expect to publish blog posts in the future with updates about our participation in the program.

The Big Idea: Gideon Marcus

2026-02-19 18:55

On occasion, you know the ending of your story before you start writing. Most other times, you find the path as you go, each twisting turn appearing before you as you continue on your merry way. The latter seems to be the case for author Gideon Marcus, who says in his Big Idea that he wasn’t always sure how to wrap up his newest novel, Majera.

GIDEON MARCUS:

What’s the big idea with Majera? That’s a hard one, because there are lots of threads: the unstated, obvious, valued diversity of the future, which helps define the setting as the future. That’s a familiar technique—Tom Purdom pioneered it, and Star Trek popularized it. There’s a focus on relationships: found family, love in myriad combinations. There’s the foundation of science, a real universe underpinning everything.

But I guess what I associate with Majera most strongly is conclusion.

Starting an exciting adventure is easy. Finishing stories is hard. George R. R. Martin, Pat Rothfuss. Hideaki Anno all have famously struggled with it. When Kitra and her friends first got catapulted ten light years from home in Kitra, I started them on a journey whose ending I only had the vaguest outline of. I had adventure seeds: the failing colony sleeper ship in Sirena, the insurrection in Hyvilma, and the dead planet in Majera, but the personal journeys of the characters I left up to them.

I know a lot of people don’t write the way I do. I think writers mirror the opposing schools of acting: on one end, the Method of sliding deep into character; on the other, George C. Scott’s completely external creation of an alternate personality. In the Scott school of writing, characters are puppets acting out an intricate dance created by the author. In the Method school of writing, of which I am a member, the characters have independent lives. I know that seems contradictory—how can fictional agglomerations of words achieve sentience?

And yet, they do! I didn’t plan Kitra and Marta’s rekindling of their relationship. Pinky’s jokes come out of the ether. Heck, I didn’t even come up with the solution that saved the ship in Kitra—Fareedh and Pinky did (people often congratulate me on how well I set up that solution from the beginning; news to me! I just write what the characters tell me to…)

All this is to say, I didn’t know how this arc of The Kitra Saga was going to end. But I knew it had to end well, it had to end satisfyingly, for the reader and for the characters. There had to be a reason the Majera crew would stop and take a breather from their string of increasingly exotic adventures. The worldbuilding! All of the little tidbits I’d developed had to be kept consistent: historical, scientific, character-related. There had to be a plausible resolution to the love pentangle that the Majera crew found themselves in, one that was respectful to all the characters and, more importantly, the reader’s sensitivies and credulity.

That’s why this book took longer to put to bed than all the others. It’s not the longest, but it was the hardest. Frankly, I don’t think I could even have written this book five years ago. I needed the life experience to fundamentally grok everyone’s internal workings, from Pinky’s wrestling with being an alien in a human world, to Peter’s coming to grips with his fears, to Kitra’s understanding of her role vis. a vis. her friends, her crew, her partners. In other words, I had to be 51 to authentically write a gaggle of 20-year-olds!

Beyond that, I had to, even in the conclusion, lay seeds for the rest of the saga, for there is a central mystery to the galaxy that has only been hinted at (not to mention a lot more tropes to subvert…)

Conclusions are hard. I think I’ve succeeded. I hope I’ve succeeded. I guess it’s for you to judge!

Majera: Amazon|Amazon (eBook)|Audible|Barnes & Noble|Bookshop|Kobo

Cover Reveal: Monsters of Ohio

2026-02-19 16:35

Just look at this cover for Monsters of Ohio. Look at it! It is amazing. I am so happy with it. It’s the work of artist Michael Koelsch (whose art has graced my work before, notably the Subterranean Press editions of the Dispatcher sequels Murder by Other Means and Travel by Bullet) , and he’s knocked it out of the park. I am, in a word, delighted.

And what is Monsters of Ohio about? Here’s the current jacket copy for it:

In many ways Richland, Ohio is the same tiny, sleepy rural village it has been for the last 150 years: The same families, the same farms, the same heartland beliefs and traditions that have sustained it for generations. But right now times are especially hard, as social and economic forces inside and outside the community roil the surface of the once-placid town.

Richland, in other words, is primed to explode… just not the way that anyone anywhere could ever have expected. And when things do explode, well, that’s when things start getting really weird.

Mike Boyd left Richland decades back, to find his own way in the world. But when he is called back to his hometown to tie up some loose ends, he finds more going on than he bargained for, and is caught up in a sequence of events that will bring this tiny farm village to the attention of the entire world… and, perhaps, spell its doom.

Ooooooooooh! Doooooom! Perhaaaaaaaps!

If that was too much text for you, here is the two-word version: Cozy Cronenberg.

Yeah, it’s gonna be fun.

When can you get it? November 3rd in North America and November 5 in the UK and most of the rest of the world. But of course you can pre-order this very minute at your favorite bookseller, whether that be your local indie, your nearby bookstore chain, or online retailer of your choice. Why wait! Put your money down! The book’s already written, after all. It’s guaranteed to ship!

Oh, and, for extra fun, here’s the author photo for the novel:

Yup, that pretty much sets the tone.

I hope you like Monsters of Ohio when you get a chance to read it. In November!

— JS

- 2026‑02‑19 - An update on upki: TLS certificate revocation checking with CRLite in Rust.

- https://discourse.ubuntu.com/t/an-update-on-upki/77063

- redirect https://dotat.at/:/6G6LO

- blurb https://dotat.at/:/6G6LO.html

- atom entry https://dotat.at/:/6G6LO.atom

- web.archive.org archive.today

Thursday reading

2026-02-19 17:19Current

The Pavilion of Women, by Pearl S. Buck

The Fifth Elephant, by Terry Pratchett

Liberation: The Unoffical and Unauthorised Guide to Blake’s 7, by Alan Stevens and Fiona Moore

Last books finished

The Doors of Midnight, by R.R. Virdi (did not finish)

Stone and Sky, by Ben Aaronovitch

The Big Wave, by Pearl S. Buck

Outpost: Life on the Frontlines of American Diplomacy, by Christopher R. Hill

The Recollections: Fragments from a Life in Writing, by Christopher Priest

Next books

De gekste plek van België: 111 bizarre locaties en hun bijzondere verhaal, by Jeroen van der Spek

The Woman in White, by Wilkie Collins

A Power Unbound, by Freya Marske

The Grail Tree, by Jonathan Gash

2026-02-19 17:02Second paragraph of third chapter:

Dusk fell when I still had about four miles more to go. needed to borrow some matches so I called in at an antiques shop in Dragonsdale, a giant metropolis of seventeen houses, three shops, two pubs and a twelfth-century church. That’s modern hereabouts. Liz Sandwell was just closing up. She came out to watch me do the twin oil-lamps on the Ruby. Well, you can’t have everything. Liz is basically oil paintings and Georgian incidental household furnishings. She has a lovely set of pole-screens and swing dressing-mirrors.

Having been rereading the Agatha Christie novels, I realised that I still had an unread Lovejoy novel from years ago on my shelves. And actually I realise now that I had read it even more years ago, but it’s short and digestible.

This is the Lovejoy of Gash’s original conception, fanatically obsessed with antiques and fatally attractive to women, who he treats badly. In fact he hits one of his girlfriends on page 2 (though in fairness she hits him first). If you pick this up expecting the gentle humour of Ian Le Frenais’ writing and Ian McShane’s acting, well, you’ll be surprised.

At the same time, I think the writer is fully aware of Lovejoy’s flaws and shows us what a monster he is, through his own lack of self-perception. And the actual plot of the book is a murder mystery, where Lovejoy is motivated by righteous rage when a friend is killed and the police write it off as an accident. I found the actual mystery resolution a bit opaque, but there is a fantastically well written climactic scene in Colchester Castle, where Lovejoy and his charming newly hired apprentice Lydia take on the villain, Lydia making her first of many appearances here.

There’s also a fair bit of lore about the Holy Grail – this book was published in 1979, three years before The Holy Blood and the Holy Grail, but after at least two of the three BBC documentaries that it drew on (from 1972, 1974 and 1979). Not to go into details, but it had me checking Wikipedia for the career of Hester Bateman, one woman for whom Lovejoy has the highest respect.

Anyway, the protagonist’s extreme sexism means that the book has aged very badly, but you can get The Grail Tree here.

Identity Digital acquires another gTLD

2026-02-19 15:19Identity Digital has bulked out its already substantial portfolio of gTLDs, taking over the ICANN registry contract for another 2012-round string earlier this month. The company is now running .onl via a newish affiliate called Jolly Host, according to ICANN records. It had been managed by Germany-based iRegistry, the original applicant. .onl — short for […]

The post Identity Digital acquires another gTLD first appeared on Domain Incite.

Visualising the past

2026-02-19 17:33For example stepping down the stairs into the lower level of Armstrong’s shop in Hawick, as I go looking for knitting or sewing supplies.

Skipping along the path on the other side of the old railway line in Melrose - now the new bypass - from my home in Ormiston Grove. I was playing with friends, and glimpsing Chiefswood in the distance.

Or my many years fun, roller skating down the steps from the seaside path above the East Sands into Albany Park where we always stayed for summer holidays in St Andrews.

I’ve seemingly developed aphantasia since, and struggle to visualise new scenes, especially when reading. But it’s nice some old visuals are still clear.

The Pudding looks at women’s clothing sizes and body types

2026-02-19 17:15All Regulations Are Written in Blood

2026-02-19 12:10PCs are field agents in charge of finding and dealing with arcane occupational safety violations. That six-sided summoning pentagram? Flagged. That storeroom where the universal solvent is next to the lemonade? Flagged.

That deadly-trap-filled dungeon abandoned by its creator when the maintenance fees got too high? Red tagged.

This isn't the same as my recent FabUlt campaign. That was about discouraging the worst excesses in a world run by oligarch mages and there weren't really regulations. This would be set in a regulatory state, and would be more an exploration of normalization of deviance.

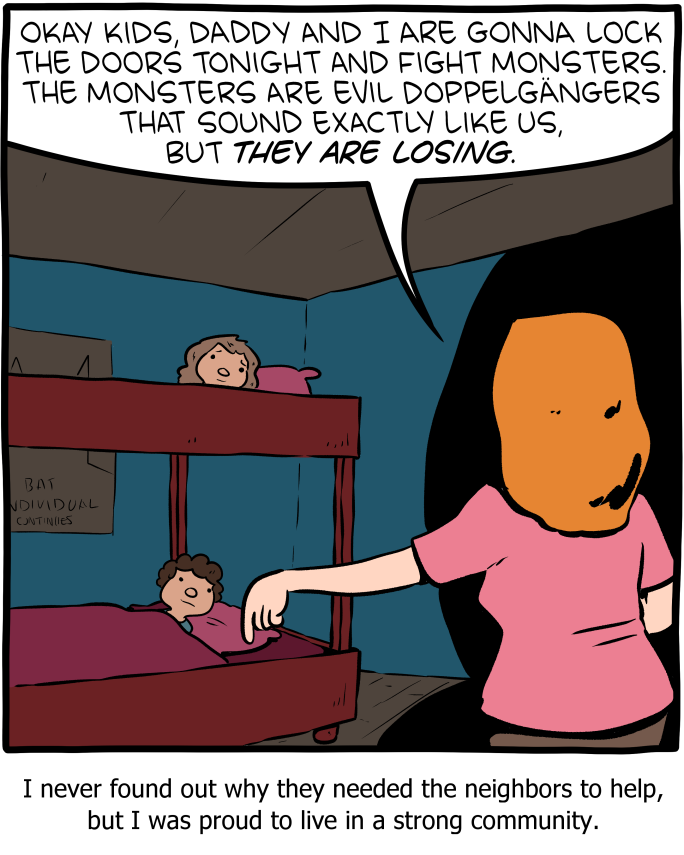

Saturday Morning Breakfast Cereal - Battle

2026-02-19 11:20

Click here to go see the bonus panel!

Hovertext:

Still don't know why they kept asking their ghostly duplicates whether they liked that over and over.

Today's News:

Unsung

2026-02-19 16:44Seven dead registrars on the out

2026-02-19 12:38When a registrar stops paying its registry partners, they tend to be cut off relatively quickly. ICANN takes a bit longer. That seems to be what’s happening to a collection of accredited registrars under the same ownership, which have been given just a few weeks to pay over a year’s worth of overdue ICANN fees […]

The post Seven dead registrars on the out first appeared on Domain Incite.

NSA and IETF, part 5

2026-02-19 13:34Slow Gods by Claire North

2026-02-19 08:52

Against the gleefully hypocritical, exploitative Shine, the very gods themselves contend in vain.

Slow Gods by Claire North